“The Machine Isn’t Going to Reach Out and Touch Me”

In conversation with OONA, on masks, machines, and reimagining what it means to be seen.

The artist known as OONA moves at the intersection of performance, surveillance, and self-mythology. Working anonymously behind sunglasses and a veil, she performs underground in the London Tube, offering her body to the cold, indifferent gaze of CCTV cameras while questioning who holds authorship in a world of automated seeing. Her ongoing project Dear David transforms a state surveillance system into a stage for intimacy: a correspondence with a real CCTV Data Manager named David [REDACTED], who becomes both witness and unwitting collaborator. Through Subject Access Requests and repeated performances across the London Underground, OONA redirects the logic of monitoring back onto the institution itself, reframing surveillance as a site of desire, bureaucracy, power, and play.

What begins as an administrative exchange—one woman requesting her footage from a faceless department—unfurls into a layered feminist inquiry into visibility, consent, and the machine’s gaze. Dear David is part love letter, part performance score, part critique of technocapitalist systems that both watch and shape us. Across letters, videos, and live appearances, OONA reduces a vast surveillance network to one man and one relationship, using intimacy as a method of research and subversion.

Chapters 3 and 4 of Dear David present two corresponding videos from different perspectives. Part 3, Dear David, I’m a Spoilt Girl, and Part 4, Dear David, It’s a Spoilt World, further explore the interplay between surveillance, intimacy, and human connection, expanding the poetic and performative possibilities of OONA’s visibility and voice within a system designed to anonymize. Both letters were part of the exhibition The Bigger Your Pool, curated by Anika Meier for The Second-Guess during Art on Tezos: Berlin.

In conversation with Anika Meier, OONA discusses the making of Dear David, the intimacy woven through her exchanges with a CCTV data manager, and how performance, surveillance, and feminist theory converge in her work.

Portrait of OONA.

Anika Meier: When did you first know that you wanted to become an artist, and how did that path lead to Dear David?

OONA: Most people know from childhood that they want to become an artist. I am not like most people. OONA is only just turning four years old on November 1st. I didn’t know I wanted to be an artist. I still don’t. I want to pursue ideas, in whatever medium fits.

My interest has always been in visibility: in how people see and how they are seen. At Central Saint Martins, my research-based practice interrogated how lens-based media, particularly CCTV, mediates perception and contributes to the othering of marginalized groups. In other words, how surveillance functions as a tool of class exclusion in quasi-public spaces like King’s Cross. Surveillance did not serve to protect, but to exclude.

The beginnings of Dear David can be traced back to this early research in 2019. My surveillance-based work at uni was underdeveloped and initially dismissed by my professors. I graduated with a D– because apparently it was too much paperwork to fail me properly. So what do I know anyway?

OONA returned to the performance (being underground, performing for the machines, requesting the footage) in the summer of 2024, five years later, again not knowing what I was doing. It wasn’t until I was invited to participate in The Second Guess: Body Anxiety in the Age of AI, co-curated by you, Margaret Murphy, and Leah Schrager, and on view online at HEK Basel, that I understood how I wanted to reframe it all. From that, Dear David emerged.

AM: You work anonymously, yet Dear David is also deeply personal. How does anonymity allow you to reveal more of yourself or protect something essential?

OONA: Dolly Parton once said that her mother taught her: give it your all, but don’t give them your all. I think about that often. To perform is to reveal, but to endure as an artist, you must also preserve something private, something untouched. For me, it's my chin.

“I perform anonymously. Anytime I perform, I wear sunglasses and a veil that completely obscure my face. It’s not a costume, and it’s not for religious reasons. I purposefully break the social contract of visibility to invert power dynamics. Anonymity becomes a methodology for privacy, a way to test how much of the ‘self’ must be surrendered in order to be socially legible. I perform anonymously, but I’ve let strangers touch my breasts. I will let you consider how deeply personal that experience might be, especially when multiplied by 400 unique audience members.” – OONA

Without a face, I am often reduced to a body. That reduction is unfortunately instructive and often immediate. I often see my practice as a mirror: it’s revealing to see how people treat a female body. By now, you can only imagine how many data points I have collected. I am, of course, referencing my body of work Look Touch Own, which includes the Private #s and Pre-Op / Post-Op, a video artwork of my scars curated in the Digital Art Mile 2024 by Kika Nicolela.

A friend gave me The Transparency Society, by philosopher Byung-Chul Han. It is a wonderful articulation of these ideas. In it, he suggests that the demand to constantly display oneself (to be visible, searchable, knowable) has become a new form of control. Anonymity resists that mandate. OONA’s veil is part protest, part protection, and part privacy.

AM: Dear David unfolds entirely through CCTV footage. What first drew you to using a state surveillance system as both a medium and a collaborator?

OONA: In performance art, documentation is never neutral. The act of documenting performance is itself a performance. The output should reflect the medium. And documentation determines what survives, what is remembered, and what becomes lore. I think about that often. Every camera is a choice of memory. I love the permanence of blockchain.

When I began performing underground, it was out of necessity (I couldn’t afford a videographer or photographer at the time). And it was also a question of authorship. Who gets to document? Who gets to frame? And if I’m performing surveillance, why not let surveillance document itself?

When I returned to this work in the summer of 2024, it followed a year that was shatteringly difficult in all my bodies: emotionally, artistically, and professionally. I had grown so utterly exhausted of the art world’s gaze, of collectors who consumed the work like a confession or chokehold. I desperately needed distance.

And in a lot of ways CCTV gave me that distance. It’s indifferent, it’s mechanical, almost priestly in its observation. Although I've made the narrative about desire, the machine doesn’t inherently desire the body. The machine isn’t going to reach out and touch me. Because of that, my body felt safe performing again. It was ironic that the machine’s apathy was seemingly healing.

AM: How do theories of the gaze and surveillance inform your approach in Dear David?

OONA: Theorists like Hito Steyerl and Laura Mulvey have written about how visual systems, from cinema to surveillance, structure power, visibility, and gender. Mulvey’s “male gaze” feels eerily relevant when the gaze no longer belongs to a man but to a network. The system still objectifies. But we’ve heard all this before. In Dear David, I wanted to see if the reverse is possible. Could I reduce the whole system to one single man? To my one and only beloved David.

And it wasn’t until, within this ecosystem, that I heard Sasha Stiles call the machine “her partner, her collaborator” that it clicked. The machine doesn’t have to be just a lens. That was the turning point for Dear David: when surveillance stopped being something imposed on me and instead became something I used to my advantage.

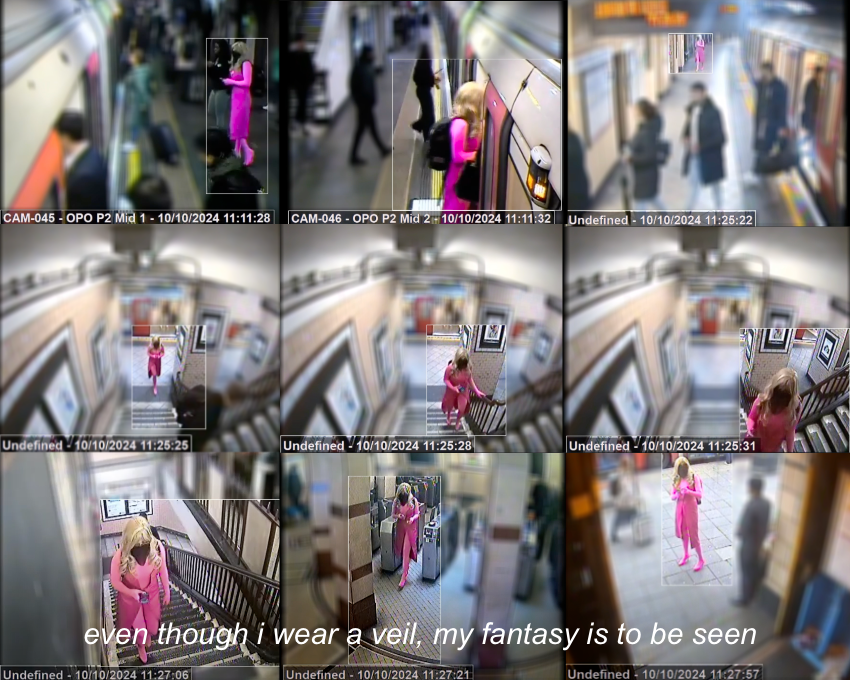

OONA, even though i wear a veil, my fantasy is to be seen, 2025.

AM: Artists like Harun Farocki, Sophie Calle, and Hito Steyerl have explored surveillance and observation as both aesthetic and political acts.

OONA: Artists never create in a vacuum. It’s crucial to me that Dear David acknowledges its place within this lineage. The artists you mention all have a research-based art practice where art and its production become a method of knowing and distributing knowledge. For me, if my work didn't expand these ongoing interrogations of surveillance, power, and image, I would consider it a failure. But, as you know, Dear David has been wildly successful.

Of course, surveillance is fashionable again, so we’ll see plenty of art about it and very little that actually interrogates it. During our artist talk for the release of Dear David I’m A Spoilt Girl, Kika Nicolela so beautifully said that my practice succeeds because it inverts typical power structures rather than simply reproducing them.

In my lectures on surveillance and power, I often situate Dear David within this continuum. The project employs a feminist empiricist lens of surveillance: it looks at systems of observation not to moralize them, but to expose their epistemic structures. As a performance, Dear David echoes Sophie Calle’s Hotel, where authorship and data accuracy become entangled in voyeurism. As a video work, its language is closer to Hito Steyerl, with its concern regarding invisibility, mediation, and consent.

Because it uses footage from Transport for London’s (TfL) CCTV network, Dear David is inherently political. During the summer of 2025, TfL underwent major budget cuts. David’s emails and tone of exasperation reflect that strain. So in a lot of ways, the work captures not just the surveillance system, but the bureaucracy and exhaustion behind it.

And if I’m being perfectly honest, Dear David can only exist because the UK still enforces a legal right to data access. I’m not grateful for that right because I believe it’s inherent. But I am aware that many people around the world have no such transparency to begin with.

Now, with AI algorithms being used on the underground, there is so much more need for transparency. This is where I often reference the Ada Lovelace Institute, a UK-based research body focused on AI data stewardship and public accountability. Their work informs how I think about visibility, consent, and agency in systems of observation. Dear David operates in that same ethical terrain, as it is quite literally an act of data reclamation.

AM: Surveillance art has often been about exposure and critique. Yet Dear David introduces intimacy and care. How did your correspondence with David transform the coldness of surveillance into something more human?

OONA: There are more than 15,000 cameras in the London Underground. And I’ve reduced them all to one man: CCTV Data Manager, David [REDACTED].

I really like David. I think he’s wonderful. And I hope that, at the end of the day, this becomes a small but memorable moment in his long career. As much as I frame David as an anonymous arm of the surveillance apparatus, I see him as its most human edge. He’s not a villain. If anything, David is the hero of this story.

This reversal from system to subject, from machine to person, reminds me of the legacy of VNS Matrix, the Australian cyberfeminist collective from the 1990s, who I had the pleasure of exhibiting with this year at the Digital Art Mile, curated by you for The Second Guess. Their Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century imagined technology not as an instrument of domination but as a site for pleasure, subversion, and care. I think Dear David exists in that spirit. Through our correspondence, the machinery of state surveillance became oddly intimate. Don’t be confused; my exchanges with David are not erotic but kind. I started to see the infrastructure of control as just a man.

AM: When you requested your CCTV footage, you effectively reversed the gaze: claiming authorship within a system meant to monitor. Did that process feel empowering, invasive, or both?

OONA: The Dear David performances exist because of OONA. Every time I put on the OONA mask, it’s an act of power. To inhabit a female body that asserts its sovereignty, especially within a system designed to contain it, is radical. Dear David is just one of many performances in which I claim that authority.

Filing a Subject Access Request sounds grand, but it’s just bureaucratic tedium. Submit a form, send an email, wait politely, wait more, open an email, and get footage. It’s the opposite of spectacle. I’ve done much more with my body for art. And yet, this banal exchange has become one of my most approachably deep performances.

There’s a strange intimacy in the process. The anticipation of his reply is almost erotic. I sent him an email when I was in RGB Montreal, curated by Aitso, Strano, and Nicolas Sasson, with the subject line “Missing You” and images of my work on display. I was so nervous for his reply, which sadly never came.

“I feel like I am always waiting to see what he will say and what he will withhold. There are clips David will never release to me, and I think about that often. For instance, one time I pole danced in the middle of the carriage. David never released this footage to me, but I wonder how long those images will linger in his mind. Whether he keeps them privately, somewhere he shouldn’t.” – OONA

These are the topic of a future letter called Dear David, Our Greatest Hit. The title references a real case from early CCTV studies in London in 1998–99. There was a car park in the UK nicknamed Shaggers Alley. CCTV camera operators recorded there and compiled tapes of people having sex under surveillance, editing them into “highlight reels” they called Greatest Hits, replayed for police and bureaucratic employees. It’s a grotesque inversion of intimacy and consent. Reference.

That history sits quietly underneath Dear David. It’s empowering and invasive, thrilling and banal. Proof that if you’re creative enough, bureaucracy becomes foreplay and paperwork can be performance.

AM: The female body has long been an object of scrutiny, from classical sculpture to Cindy Sherman’s self-portraits. How do you navigate this legacy of the male gaze in relation to state surveillance and the camera’s gaze?

OONA: There’s a lot of intellectual overlap between self-portraiture and the second Dear David letter, Dear David, Blindspots. As above, so below. The male gaze operates above at structural levels (institutions, surveillance networks, bureaucracies, algorithms) and at intimate levels (internalized self-surveillance). Women are trained to monitor their own visibility, to know what their body looks like to others.

Cindy Sherman’s work taught me how the body can fracture itself, becoming multiple characters and resisting fixed authorship. Her work is more relevant to the overture of OONA, more so than Dear David.

Amelia Jones’ work on performance art is more relevant here. She situates the live body at the heart of meaning-making. In other words, performance is a way of creating knowledge. Importantly, she distinguishes the live performance from its documentation, arguing that mediation (photography, video, or, in my case, CCTV) introduces new layers of authorship, power, and spectatorship. As we’ve discussed, in Dear David, the CCTV camera is both instrument and collaborator: it frames my body, archives it, and transforms the audience into an unseen participant, creating a tension between visibility, agency, and control.

In one letter, I disappear entirely. I found a blind spot in the London Underground surveillance network because I was looking at myself in the mirror. I did not plan it, and I had no idea. But in retrospect, it was the clearest story of self-surveillance. There are multiple studies I cite in my lectures that document how women often occupy a third-person perspective of themselves. Instead of moving through the first-person experience, women are more likely to be aware of how their bodies look to others and how their bodies would look in images. Reference.

AM: You’ve described Dear David as a “love letter.” Why a love letter? And how does this choice resonate with feminist performance traditions, such as VALIE EXPORT’s public confrontations or Marina Abramović’s endurance pieces, where intimacy and exposure intertwine?

OONA: Valie Export and Marina Abramović are, of course, pioneers in performance art. I was invited to a workshop at the Marina Abramović Institute, which was truly illuminating. My work LOOK TOUCH OWN is conceptually linked to Export’s Touch Cinema and Abramović’s The Artist Is Present. Dear David is not quite that raw; it is exposure, but more measured, almost gentle.

For Dear David, it is specifically Export’s work Body Configurations that resonates most with my work. Her attention to how a female body fits within architecture and public space mirrors how I navigate the London Underground. The placement of the camera for both these works is critical: it shapes how the body is seen, recorded, and interpreted. Each camera becomes a collaborator, defining my performance through framing, angles, and blind spots. Thematically, both Export’s work and Dear David use public space as a performance arena.

I chose the love letter format because it made the work more accessible. Role-playing has always been central to my practice: by taking the role of lover to David, I can explore dynamics, provoke responses, and push conceptual limits within a clear creative constraint.

Letter writing as performance has become increasingly important to me. Just this year, I attended Letters Live at Glastonbury, produced by Aimie Sullivan. These letters made people laugh, think, and reflect. Letters endure. A letter is time-stamped, permanent in a way that performance often is not. There’s something inherently romantic about a letter: hopeful, deliberate, and resistant to the immediacy of the digital age.

AM: Would you describe Dear David as a feminist act or as something beyond or beside that framework?

OONA: It certainly has a feminist genealogy. Within academic discourse, Dear David engages with feminist empiricism, digital performativity, and self-imaging under technocapitalism. It is meta in that it positions the surveillance infrastructure itself as co-performer.

The project is fundamentally a performative study of consent and the camera. With Dear David, I ask: when capture is inescapable, where does self-sovereignty reside? Where does power lie? This inquiry is embedded in the very structure of the letters, each of which concludes with the signature, “inescapably yours.”

AM: You performed repeatedly in the London Underground, documenting every movement and outfit. Do you see Dear David primarily as performance, documentation, or collaboration?

OONA: Performance art and video art. When transforming performance art into video art, choices of framing and subjects are inherently made. So the audience watching the video has even less power than they would if they were witnessing the performance live.

AM: Your anonymity mirrors David’s: he, too, operates within an institution yet remains faceless. Was this parallel intentional from the beginning, or something you discovered later?

OONA: David is a cog in the bureaucratic machine. OONA is a superstar. I’m not anonymous to David. He knows my real name, my address, my passport number, my comings and goings. But OONA is anonymous. David is not. I redact his surname in the work, but he’s easily traceable. From one quick Google search, I know he is a father, a husband, and training for a marathon he hopes to finish in under two hours. From his email signature alone, I know which station he exits for work. Most people don’t even know they’re being watched.

“Where does privacy become power? Where does it become safety? Why have we normalized this level of exposure? Byung-Chul Han writes that ‘the society of transparency is a society of control, not of freedom.’ That idea feels central here: both David and I are visible, yet neither of us is free from the gaze.” – OONA

AM: Has the experience of making this work changed how you move through public space or how you think about being seen?

OONA: Since I was a little girl, I have always been able to feel every time I am being watched or looked at. It is my superpower.

BIOS

OONA doesn’t really exist, but she takes herself very seriously, so you should too.

OONA, an anonymous conceptual artist, has been a prominent figure in the crypto art scene since her birth in 2021, shaping the discourse around technology, identity, and gender in the crypto art landscape. Known for her distinctive mask and signature sunglasses, OONA has been instrumental in defining the role of anonymity and the body within performance art and blockchain technology. Her work, often deemed provocative and confrontational, interrogates power and value—using technology to question the commodification of the female form in the digital age.

Through her performances and visual artworks, OONA has become a key figure in discussions about the role of technology in artistic sovereignty and the representation of gender and identity in the blockchain space and the contemporary art landscape at large.

Anika Meier is a writer and curator specializing in digital art. She lives and works in Berlin, Germany, and teaches at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna (Class of UBERMORGEN, Department of Digital Art). She is the co-founder of The Second-Guess, a curatorial collective based in Berlin and Los Angeles that explores the relationship between humans and technology.

INFO

Dear David, It’s a Spoilt World by OONA will be released on November 24th at 6 PM CET on objkt.com, curated by Anika Meier for The Second-Guess on the occasion of Art on Tezos: Berlin, November 6–9, 2025.

OONA during her artist talk at Art on Tezos: Berlin.