Long-Form Creativity

“Sometimes you need to separate the art from its market to measure its relevance.” - Marius Watz

Marius Watz at MoMI.

Marius Watz’s story is intertwined with the more recent history of generative art, dating back to the mid-2000s, when a “new aesthetic” was emerging across Europe — visually fresh, rooted in the early explorations of Processing, with artists using code to create systems that produced visual abstractions. “They were developing a formal language native to code, complete with semiotics to describe the ideas they were exploring. Net art, glitch, and minimalist generative systems were all products of that process of discovery,” explains Watz, an artist, curator, and educator based in Oslo, who presents his first long-form generative art drop on objktone on September 4, alongside Aleksandra Jovanić.

Watz has been making art with code since 1994 and is known for his hard-edged geometrical forms and vivid colors, with outputs ranging from purely software-based works to public projections and physical objects produced using digital fabrication technology. His work has been exhibited worldwide, in major institutions from the Victoria & Albert Museum (London) to ITAU Cultural (São Paulo).

From the Generator.x platform to his iconic Exploder (2009) at MoMI in 2025, exhibited under the curation of Regina Harsanyi, in this interview the artist unpacks the deep knowledge and experience that only a true OG possesses. A sharp mind - check out the conversation.

Raquel Gaudard - I first came across your name through Generator.x a long time ago—maybe around 2006, or a little later? And, of course, in the book Digital Art. But anyway, back then, during my early research on new aesthetics, people weren’t as into social media, so I confess I spent more time exploring the web, finding cool blogs and platforms like Generator.x. What happened to it?

Marius Watz - Generator.x… that’s a long story. These days I don’t expect people to know much about it, Generator.x 3.0 (at iMal, Brussels, 2012) was the last event in the series and the blog went dark around 2015. I have the blog data archived, but never had the time to put it back online. It’s a historical document by now, so I should get it back online (though I might cringe at some of my writing.)

Most people know Generator.x as a blog, but between 2005 and 2012 Generator.x I curated a series of different events around Europe - exhibitions, concerts, workshops etc. The idea was born in 2004 to establish a broad platform for discourse around generative art and the expanded field of computational aesthetics. From the start the stated intent was to track emerging trends across art, design and architecture, including data visualization, live visuals and so on. Later editions focused on digital fabrication and brought together artists and architects working on similar ideas, co-inventing a language for generative systems across different conceptual contexts.

Generator.x 2005 poster.

The core hypothesis of Generator.x was that by embracing code and software as a native language of digital practice, artists and designer were coming up with new aesthetic forms and models for creative work: Terms like generative art, creative coding or parametric design may come from disparate theoretical contexts, but ultimately are all expressions of similar ideas about a shift from static objects to dynamic, semi-autonomous systems. From digital media as literal translation of physical artifacts towards a software model, in which computation and algorithms become an integral element.

Compared to “software art” (argued by Inke Arns, Florian Cramer etc. around the same time), Generator.x.was less concerned with a critique of software as a cultural / political artifact, than with the implications code had for creative expressions. The explicit focus on aesthetics was seen as a bit naïve in the context of European media art in the 2000’s. But my goal from the start was to promote the idea of generative art and computational aesthetics as a legitimate topic for research. The Generator.x blog (originally a PR channel) became a way to articulate my own thinking by writing “out loud”.

Also remember that this was 2005, a time of relative technological innocence. It was just two years before the emergence of the iPhone, the first mass media device to expose non-experts to software as a cultural medium. No one could have predicted the consequences we see today in our always-online, pathologically connected, data saturated reality.

Generator.x was never a formal organization, in reality it was just me. Events were made possible by partnering with existing organizations for funding, infrastructure and production. The original 2005 conference in Oslo was attended by more non-Norwegians than locals, and was made possible by the incredible support of Atelier Nord. An independent but state-funded hub for digital culture, Atelier Nord entrusted me with almost complete creative liberty to develop the concept, while also providing an institutional frame.

The conference was accompanied by a Generator.x exhibition, touring for one year with the National Museum of Norway. The exhibition featured Lionel Theodore Dean, Ben Fry, Jürg Lehni, Golan Levin, Lia, Trond Lossius, Sebastian Oschatz (Meso / VVVV), Casey Reas and Martin Wattenberg. Many of them came to Oslo to speak at the conference.

Generator.x was early in the history of the “new wave” of generative art post-2000, but it was certainly not the only blog exploring these ideas. Paul Prudence actually started his Dataisnature blog before Generator.x, and was a constant inspiration slash rival in covering new work. Paul is an amazing researcher and archivist, I’d love to see someone ask him to curate a show some day.

System C, 2006, by Marius Watz

RG - Speaking of new aesthetics, from your perspective as a curator, or also as an artist, what do you see today in digital art that feels aesthetically new to you? Whether in Web3 or beyond its bubble.

MW - AI is undeniably the big radical agent of the moment, disrupting creative practices across the board and challenging fundamental assumptions about authorship and creative production. I grew up with AI dominating the realm of science fiction, but I would never have anticipated that it might manifest as a universal image synthesizer or a generator of mindless corporate text.

I don’t think we’ll know the ultimate impact of AI for some time, but I fear the commercial effects. Tech disruption driven by venture capitalist hunger tends to not linger over any negative side effects, Spotify being a prime example. AI will no doubt kill some markets for creative work, no client will pay for “stock art” (editorial illustration / photography) when they can produce it themselves. Graphic design was already endangered after the death of print, and AI should be able to automate it into near-extinction.

Ironically, I don’t think it will impact artists as harshly, art as a commodity relies on experiences that feel authentic to the audience and so tends to reject mass-production. Creatives will find a way to establish a symbiotic relationship with AI, but just as it’s doing for developers it might tighten the margins and make art and design viable for a smaller group of people.

AI will no doubt give us new tools for creative expression, along with pop culture fads that come and go. (Shrimp Jesus? 15 seconds of fame.) I always worry about artists paying the rent, but I also enjoy the weirder expressions of AI art. And there are already plenty of serious artists innovating with AI as a co-creator or conceptual production tool.

Another big change is the NFT economy, a Faustian bargain between art and capital with all the charm of an Internet subculture. NFTs are hardly a perfect way to experience and disseminate art, but it has catapulted digital art from a niche market to being a regular topic at art fairs and auctions, with regular writeups in mainstream art publications unthinkable 10 years ago.

Specifically, generative art and NFTs have been something of a perfect match. The introduction of long-form mechanics and collector acceptance of natively digital formats has removed some of the obstacles that historically made it so hard for generative artists to find collectors. The 2021 boom alone produced a super-charged period of recruitment and innovation, with hundreds of new artists emerging in a single year. Most of them have since faded from view, but in the art world it’s fairly typical for most emerging artists to not make it past the 5 year mark.

The biggest downside I see with NFTs is how they devalue physical exhibitions as arenas for experiencing art. The immateriality of NFTs is a great advantage in terms of making them instantly viewable (and transferable) to viewers anywhere. But it also limits how they are experienced, depriving artists of the chance to create a context for the work. You might enjoy Andreas Gysin’s work online, but seeing it displayed on a physical flip-dot display is a qualitatively different experience.

In terms of pure aesthetics, I’d say that the early 2000’s generative art scene I came up with had a more minimalist or glitchy aesthetic, with less ornamentation and visual finish than is common now. This is in part due to advances in tech, computers keep getting more powerful and techniques like GPU shaders enable new styles of expression.

Exploder at OBJ, National Design and Craft Gallery, Ireland, 2018.

RG - What do you think is still missing in how generative art is contextualized for broader audiences?

MW - I think generative artists got an inflated sense of self-worth with the NFT bubble, at the end of the day it’s just another way of creating art. I’m a generative artist, I’m biased to think it’s a significant idea in the age of technology, but it’s still a continuation of a long history of abstraction. Sometimes you need to separate the art from its market to measure its relevance. A lot of Artblocks projects made bank, but the real test is whether people will be cherishing them 10 years from now.

In terms of reaching beyond their own niche, generative artists would do well to remember that the creator of an artwork tends to inhabit a cultural situation that is not shared by its potential consumers. That’s not unique to digital art, painters and ceramic artists face the exact same disconnect. I believe in giving audiences a way to approach the work, without requiring them to understand every nuance of how it was created. Not by dumbing it down, but by refraining from needlessly alienating the viewer.

Audiences are more than willing to take their time with an artwork and even read the wall text, as long as there is some kind of hook to pull them in. The basic concept of a generative system isn’t hard to grasp, audiences tend to be fascinated by the idea of a system that can give birth to a wide range of outcomes. Leaving space for the viewer to have their own experience is an essential part of showing your work to the world.

Remember: The best way to ruin a poem is to insist on explaining it.

MoMI installation, 2025.

RG - A question I like to ask generative artists: long form or short form? Why?

MW - It’s hard to explain just how alien an idea long-form used to be. I remember proposing an idea in 2008 for a project very much along the lines of a long-form generative project, an edition of 100x 1/1s with each edition generated on demand for the collector. The response from the gallerist was essentially, “Why on earth would you do that?” (Yes, really.)

As you know, Exploder is my first “proper” (i.e. mintable) long-form project. But my practice has always been based on software that can produce infinite variations, with projects from 15+ years ago that fit the basic format. Most of my works (Neon Organic, Illuminations, System_C, Blocker etc) were shown as realtime software, generating an endless series of images that were never stored.

It grates a bit when people describe the way I used to make outputs as “artist curated”, especially since it implies images of lesser value than those produced by a standalone system. But with no interest in a single software generating a large series, I never took the extra effort to polish any system to a point where it could be fully autonomous and constrained to “good art, every time”. The closest would be System_C (2003-2006), which took an hour to draw an image when exhibited. An hour per image, 6 hours a day, for weeks.

People have also forgotten Written Images (Martin Fuchs and Peter Bichsel, 2011), which was a long-form book of generative art, each copy printed on demand as a unique copy. Dozens of artists contributed software that would generate pages when executed, prescient of NFT minting in certain ways but lacking the built-in marketplace of blockchain.

Now, long-form is a logical match to the inherent nature of generative systems - why make one image when your work is an image machine? Larger editions of 1/1 are conceptually elegant and clearly attractive to audiences, a perfect storm when combined with blockchain. There is also an inadvertent slot-machine gambling effect or, to put it more generously, a sense of audience participation. Collectors are motivated by their connection to a piece, so what could be better than them causing it to spring into being?

It is also an almost scarily effective market mechanism. It shreds the standard gallery logic of selling a limited number of expensive pieces, in favor of a model more like crowdsourcing. Offering hundreds of unique pieces at a price level within reach of even amateur collectors is a genius move, I think it could have been successful even without the crypto boom. Long-form projects have achieved numbers that established mid-career artists will find it hard to reach in a lifetime of work.

In conclusion, long-form is a wonderful idea that I wish had been acceptable circa 2010. I might also wish the scene had more bandwidth for how generative art didn’t start in 2021 and that there is more to its history than Vera Molnar and Tyler Hobbs. But as I tell students, memory is fleeting and success as an artist is often a matter of timing.

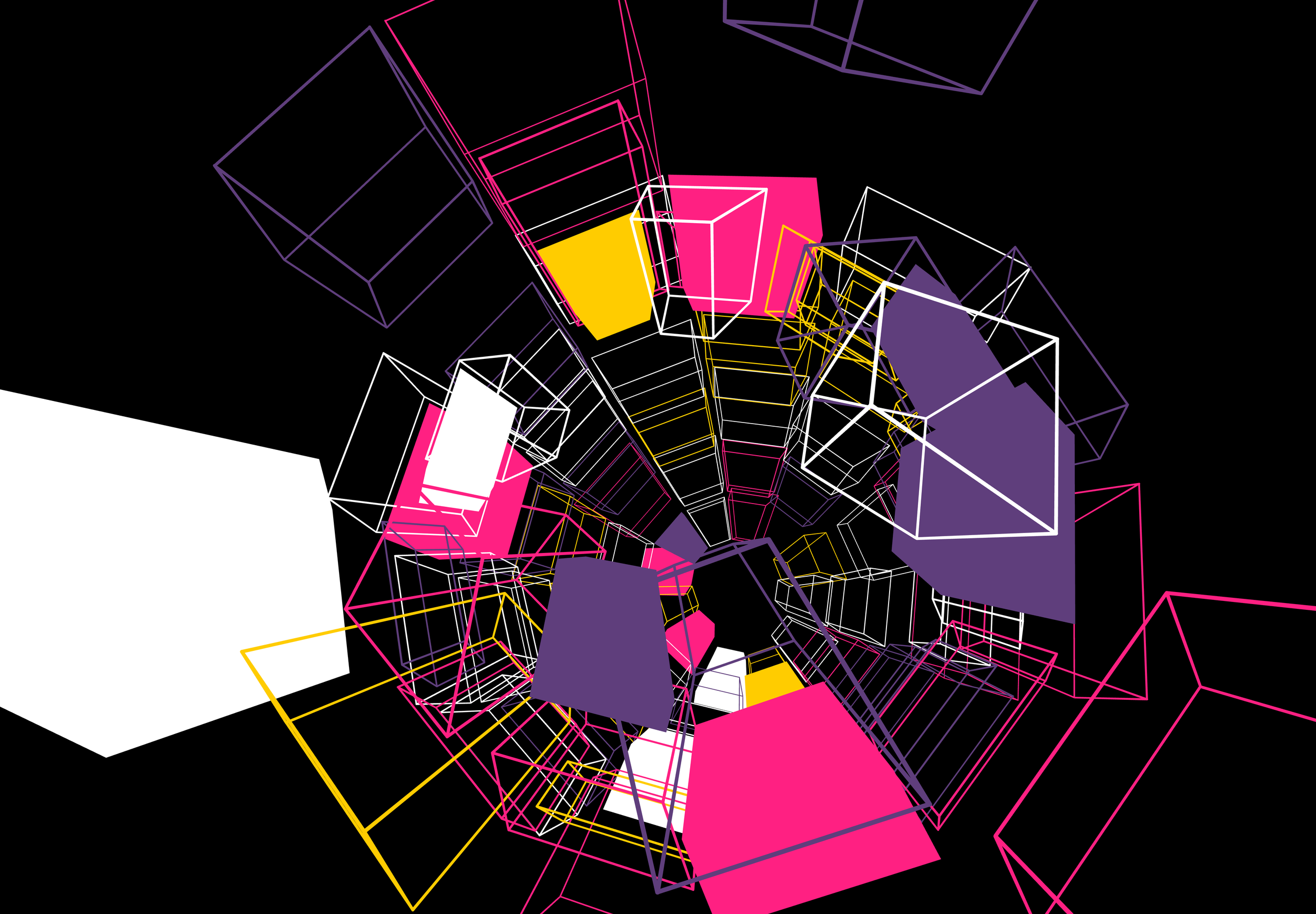

Exploder, by Marius Watz, and Returns, by Alexsandra Jovanic, at MoMI, 2025.

RG - Regarding the exhibition at the Museum of the Moving Image, Compositions in Code: The Art of Processing and p5.js, how was the process of selecting the piece you’re exhibiting, MoMi Exploder? When you're in the artist role, do you also give some curatorial input in the show? How does that dynamic work?

MW - To be clear, I haven’t curated in a decade, so curator isn’t a label I use much anymore. The artist slash curator combo is frowned upon, you can get yourself in trouble with conflicts of interest and perceptions of nepotism and self-promotion.

When Regina Harsanyi (the curator at MoMI) asked if I had any artist in mind to pair up with, I immediately thought of Aleksandra. We had never met or spoken before, but we had bumped into each other on Twitter, of course. I’ve also followed her releases over the last few years, seeing her develop a distinct voice doing her own thing. She also checks the box of using p5.js and coming to the Processing community a bit later than myself, not technically a different generation except in that limited context.

Aleksandra’s work resonates with mine in both obvious and not-so-obvious ways. We’re both influenced by references from design history (whether Bauhaus or 90’s deconstructivism), we tend towards a clean, graphic type of minimalism and color is always an essential aspect of the work. I don’t think our work is actually similar, Aleksandra’s enthusiasm for data visualization is another shared interest. I was part of that scene for a while and it was a specific topic of Generator.x under the rubric “The Beauty of Numbers”.

As for choosing Exploder, I showed it to Regina during our first studio visit, and we quickly agreed on it being a good choice for the MoMI show. Regina actually wanted an older piece for historical reasons (Exploder is from 2009), but we agreed that the narrative of “escaping the screen” is still compelling.

I developed Exploder as a signature piece for solo shows in Oslo and San Francisco (2010-2011), and it hits some important conceptual notes for me. A relatively simple (but expressive) geometric abstraction that makes no attempt at representing anything outside itself, I developed it to exploit the mechanism of projection as an integral component. Not as an optical illusion but as a way to translate a virtual form into physical space, using cheap materials to brute force itself into existence.

The imperfections resulting from drawing straight lines with artist tape are an important part of the work. The fact that the drawing is site-specific and impermanent is also a comment on the underlying software system, constantly shifting to new constellations.

Exploder at MoMI, 2025.

Kika Nicolela - And how was the process of adapting Exploder to a long form generative piece - which will be your first long form release?

MW - The long-form aspect hasn’t been a challenge, my early software works had a similar subtext about producing a wide range of outputs with distinct traits. I’ve already spent years hanging out at the edge of parameter space, hunting for interesting outputs where the system becomes unpredictable and chaotic.

Still, a realtime animation implicitly suggests a different expressive intent and viewing situation than a static wall drawing. Recreating the system from scratch in p5.js wasn’t too hard, I know it so well it’s practically a case of muscle memory to add in the little algorithmic quirks that makes the piece work.

Setting up and tinkering with the animation logic and camera movement was the biggest challenge. Trying to anticipate how randomized viewing angles, rotations and scaling would affect the composition that the viewer will experience requires a lot of testing to get right. You want moments that surprise you and make you see the piece in a new way, but you want to avoid getting 15 seconds where the entire screen is taken up by a box passing too close to the camera.

Color was another aspect I needed to consider. The original wall drawings took the color of the artist tapes used (blue / orange / pink / black), with at most 3 colors. I wanted to stay true to that aesthetic for most of the outputs, but ultimately I decided that I wanted to explore the dynamic color logic a software system makes possible. Which immediately took me down a rabbit hole of curious color schemes that will only show up in a minority of mints..

I hope viewers will understand the reason for this disconnect between the original tape drawings and the special color versions of the software version. If they choose to activate the wall drawing mode (yes, that’s in there) some of those graphic refinements will revert to straight wireframe lines again.

Exploder, by Marius Watz.

RG - What does a typical day look like for you as an artist? I know you’re also involved in education and curation, but when you're creating with code, do you have a specific routine? Do you start with a clear idea, or is it more about experimenting and seeing where it leads?

MW - Pardon the cliché, but I’ve always prioritized aesthetic intuition over planning. My pieces typically start with a simple idea of a gesture or a movement in space, then I explore how that idea evolves once I try to express it in code. Often I end up somewhere unexpected, having abandoned the original concept entirely to pursue some interesting side effect of the code.

I also have periods where I’m iterating on some larger idea or exploring a material process like 3D printing or plotter drawings. Working within arbitrary confines can be surprisingly productive. This last year I have been experimenting with an A3 plotter, testing different concepts to see what feels right.

Exploder is also a clear example of this creativity-from-confines process. It started with the search for a mechanism that would let me translate a software system into physical space as a large-scale presence. Once I zeroed in on the idea of using tape and projected wireframes, the Exploder system quickly came to mind.

RG - You’ve been in this space since the beginning, so you have the big picture: at this point, are we just mirroring the traditional art market? And from an artist’s perspective, what are your main critiques of Web3 right now?

MW - I’m always happy to see artists get paid. But the relative affluence of the NFT scene (even if notably down from 2021) introduces a disparity with the rest of the art world that isn’t trivial. Painters who have spent decades on their craft have no guarantee of selling their work for >$10.000, but in 2021 several of the best-selling artists globally were NFT artists the art world had no knowledge of, selling to collectors that were equally mysterious (and sometimes anon.)

This is certainly a funny situation with much potential for schadenfreude, especially for someone like me who had no way into the art market for my first 10 years. But most artists would benefit from not being pigeon-holed as “NFT artists”, even if that was a good thing to be for a while.

I think we’re seeing a market correction that could leave a lot of NFT artists unable to pivot, with a sudden re-emergence of the “professional” artist class among those who did so well under the punk attitudes of 2021. Without those credentials, artists might find it hard to land with the similarly re-emergent gallery system.

Personally, I was amazed and joyful seeing the explosion of new artists and projects incentivized by the 2021 boom. I have friends who became actual millionaires from generative art. But there are of course negatives, too.

Speculation is rarely good for art itself, even if I love the financial transparency that blockchain brings. The “Grails” narrative struck me as either cynical or misguided, always strange to see collectors loudly making predictions about the future markets of artists they happen to own.

I would also hesitate to declare an artist with less than two years of exhibition experience an OG, or guarantee that their work will stand the test of time. My experience is that most art is for right now, and even when not, conservation is a tough issue to handle. Digital art certainly faces some interesting challenges in that regard.

Finally, I’m sorry that the cultural default of NFT marketplaces isn’t seen as complementary or implicitly connected to shows in real spaces. I’m well aware that most of the art you ever see is as a JPEGs, but the test of showing work in physical spaces is good for artists and allows for a very different experience of the work.

I was “raised” in a media art scene filled with massive installations, large projections and rooms vibrating with sound. For digital art to be reduced to only work that can be viewed in a browser is short-sighted. But exhibitions require funding, which is why Europe and Asia have been dominant when it comes to physical digital art, simply as a consequence of cultural funding.

Exploder, by Marius Watz, and Returns, by Aleksandra Jovanic, will go live in a long-form generative drop on objkt.one on Thursday, 4 September 2025.

For more: mariuswatz.com | objkt.com/@mariuswatz