Absorbing Time: A Conversation with qubibi on ‘hello world’

“I think I’ve personally been saved by that experience — by having time absorbed away from me. That’s the deepest core of ‘hello world’, and that part has never changed.” qubibi

This conversation between artist Kazumasa Teshigawara (qubibi) and Kika Nicolela took place in the days preceding the opening of hello world, qubibi’s solo exhibition at Galerie Met in Berlin, opening on October 31, 2025, alongside a related NFT drop on objkt.com. The exhibition presents new iterations of hello world — a generative work first created in 2010 — exploring its evolving temporal and visual language through prints, videos, and a live algorithmic projection.

In this exchange, qubibi reflects on the origins of hello world, the long devotion to its algorithm, and the quiet metamorphosis that continues to unfold within it. He speaks of process as discovery, of boundaries that emerge and dissolve, and of time as something that can be “absorbed away.” The dialogue reveals an artist who listens closely to the material intelligence of code — one who approaches technology as a living collaborator in the endless act of becoming.

KN: Could you tell us about the circumstances and inspirations behind the creation of the first version of ‘hello world’ in 2010?

qubibi: Until then, I had been working as a designer and art director. I was always creating things with my own hands, but mostly through client work. Even when I was asked to make something “artistic,” it was still based on client requests — that was basically what my work looked like around 2009.

In 2009, I shot a video of “a person continuously sleeping,” which became my first self-initiated work as an artist — Swimmer. At that time, Yugo Nakamura, known as a pioneer of digital art as well as a director/designer, had just launched a digital art label. He said to me, “Teshigawara-san, why don’t you make something (for this label)?” That’s how I released my first artwork there, and hello world became the second.

I used to love manipulating colors in Photoshop. For example, in film development there’s a technique called “burning,” which enhances contrast dramatically. You can do something similar in Photoshop. And, of course, anything you can do in Photoshop, you can also do through programming.

When you take a single gradient image and sharply increase the contrast, a kind of boundary line starts to appear in the middle. It’s a simple effect to reproduce — that’s how the line emerges.

That in itself was nothing special, but I found it fascinating.

It wasn’t about drawing the line I wanted to draw, but rather that by doing something far away, a line would emerge. The idea of shaping a form through that kind of indirect process really intrigued me.

I started thinking about what that feeling reminded me of, and recalled something from my teenage years, when I used to work for managing microscopic (plant) photographs. Using a magnifying lens, I’d look very closely at a subject. From a distance, its outline would appear clear and distinct, but as you zoom in, it naturally becomes blurred. Getting closer means it blurs. Even human skin, the closer you look, the softer it appears. It only looks sharp because you’re viewing it from afar.

So I began to think — when a boundary line appears, it’s a result of distance, and when that line becomes blurry, it’s a result of closeness. It felt like a kind of universal principle: something that applies to human relationships as well. Through playing with colors, I was learning things like that.

At the time, I was using Flash, experimenting with programming to achieve similar effects. And of course, Flash allowed me to try far more than Photoshop ever could. The boundary lines that emerged through those experiments eventually led to hello world.

As my second self-initiated work, hello world marked a turning point. Once I started making it, I stopped taking on other client works and became completely absorbed. For about six months, I barely spoke to anyone, just kept creating at home or on the train. I was also making the music for it during that period. In a way, it was the beginning of me stepping off the usual path.

KN: How many times, and in which situations, has ‘hello world’ been exhibited? I would love to know its timeline over the years.

qubibi: hello world was released in 2010 through “SCR,” the digital label founded by Yugo Nakamura, whom I mentioned earlier. There wasn’t an exhibition at that time, but the following year, the work received an award at the Japan Media Arts Festival and was shown at the National Art Center in Tokyo.

Nakamura was also developing a product called Framed — essentially a display with a built-in computer, where the display itself functioned as an artwork. We incorporated hello world into that device and released it as part of the Framed lineup. We also held a small show in 2012 titled hello world Exhibition.

In the ever-accelerating web space where mutual referencing leads to sameness and uniformity, the work of Kazumasa Teshigawara continues to stand out as truly singular. His groundbreaking creativity and forward-thinking approach first captured wide attention across the web with his series of websites ‘Weave Toshi’, launched in 2004. Since then, he has continued to carve out his own distinct path with unparalleled works such as ‘INDIA’, ‘Swimmer’, and ‘Today’s Smile’.

As the first installment in the Framed©︎ Exhibition series—an exhibition platform that uses the Framed©︎ interior device as its canvas—this show presents four generative animation pieces by Kazumasa Teshigawara under the title hello world. Regarding this series, Teshigawara explains:

“The dense clusters of holes in a pancake eventually merge to form one large maze. I placed the idea of ‘boundaries,’ which can be found in all phenomena, at the core of my expression and named this animation method hello world, which generates unique images in real time. A scene of endless transformation without human intervention—what will emerge, what will be woven? Through this series, I hope viewers will enjoy the simple act of observation itself.”

There is always a mysterious pull in Teshigawara’s work—one that draws the viewer into an intimate one-to-one relationship with the display. We invite you to visit the exhibition and experience his singular world firsthand.

(Yugo Nakamura, Director of Framed©︎)

Excerpt from the exhibition pamphlet

In that pamphlet, there’s a line from Yugo Nakamura that says, “There is always a mysterious pull in Teshigawara’s work—one that draws the viewer into an intimate one-to-one relationship with the display.” I feel that it really captures something fundamental about my work. It gets right to the essence of it.

After that, in 2016, I held an exhibition in Niigata Prefecture, in northern Japan's agricultural area, using the second floor of a sake brewery. Not many people came, of course — there was no announcement, and who would imagine something like that happening above a brewery? Haha. But it was wonderful. The sweet aroma of sake was always in the air, it was the perfect environment.

After that, I participated in a small group exhibition in Munich — though I don’t quite remember the details.

Then, from 2017 to 2018, I had a solo show titled qubibi exhibition at MuDA (Museum of Digital Art) in Zurich, Switzerland. It ran continuously in the room at the very back. In many ways, that could be considered the first true exhibition for hello world; it lasted for quite a while. MuDA was unique in that it opened as the world’s first museum dedicated to digital art, even before the NFT boom began. The curator and everyone involved were wonderfully crazy — in the best way.

In 2021, I also held a solo exhibition in Tokyo titled Worm Fabric (ミミズの反物) , where hello world was shown alongside other works.

In the NFT space, I only released a few pieces from hello world. Some captured GIF animations on a platform called HEN. I think “HEN (Hic et nunc)” stood for “Here and Now.” Since most of my NFT releases have centered around works like mimizu and door, many people in the fast-moving NFT world probably don’t even know about the old hello world.

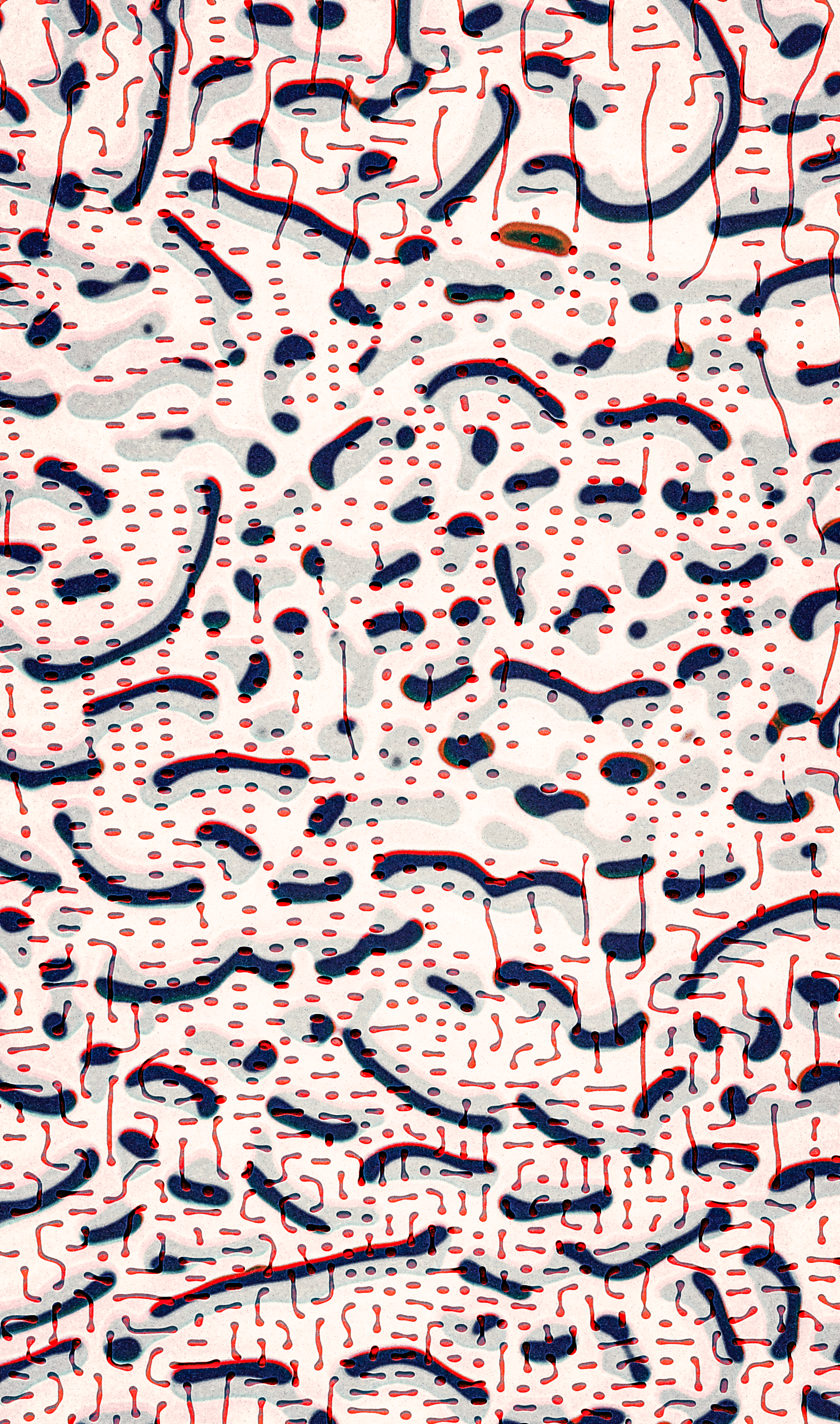

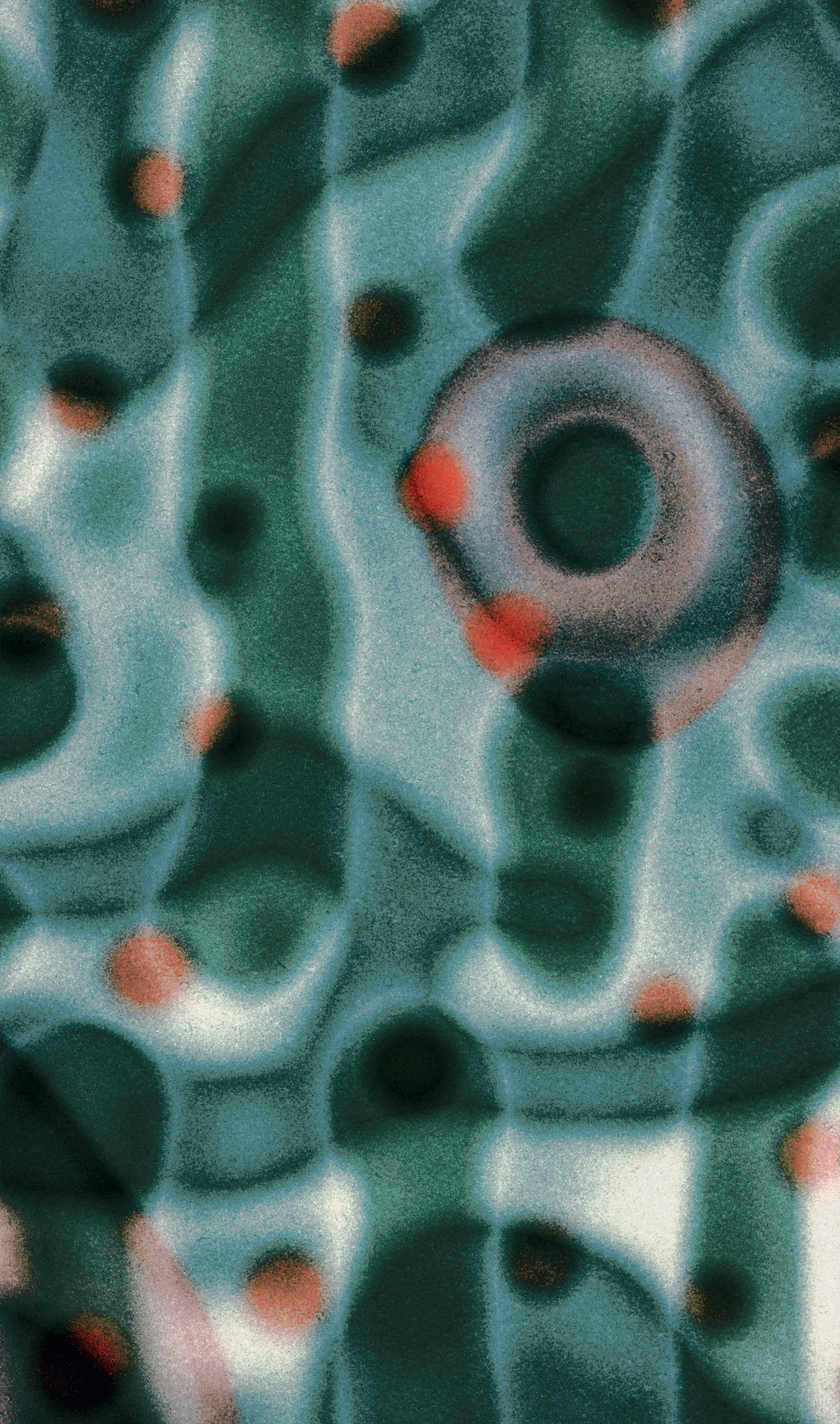

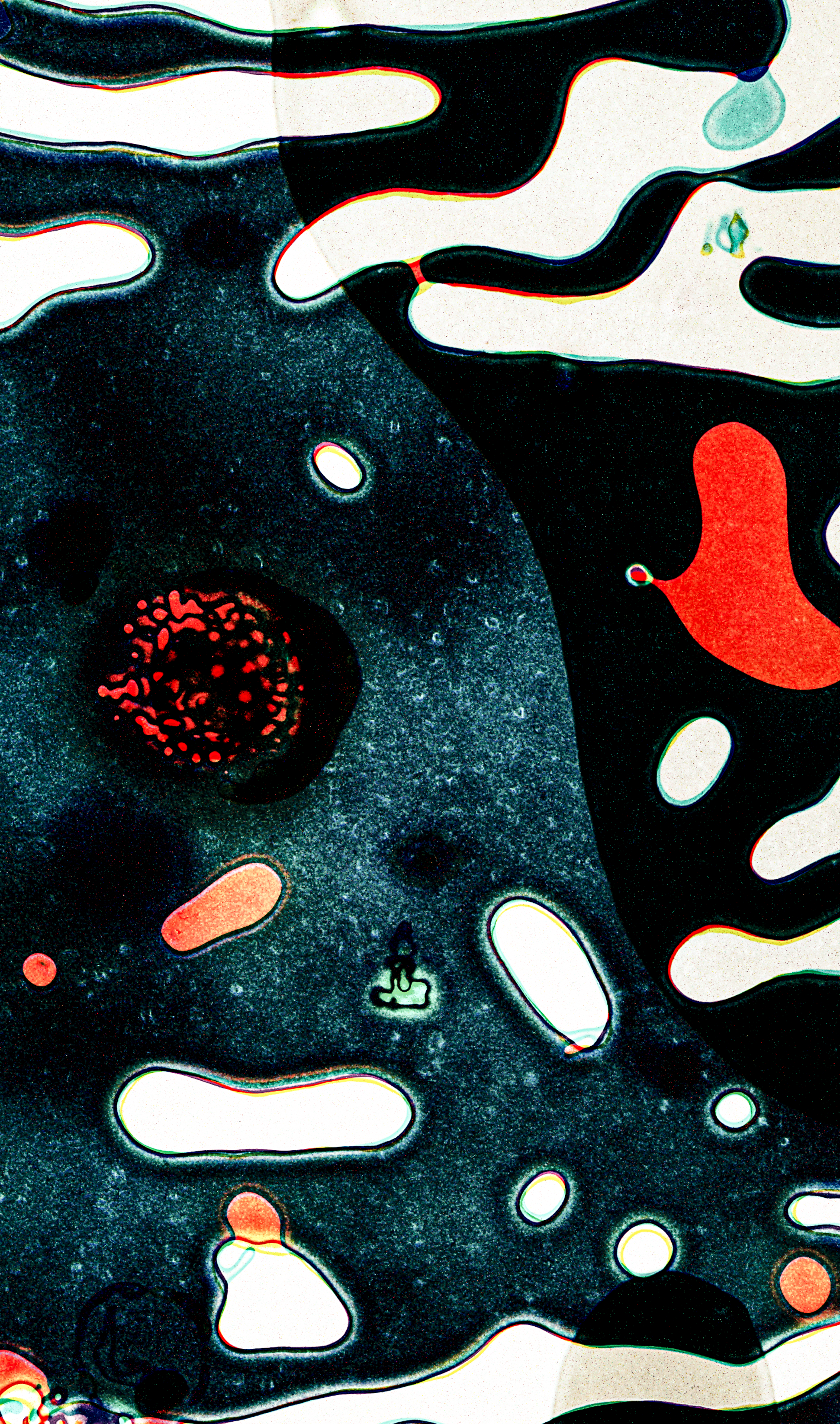

hello world (2025)

KN: Why do you keep going back to this algorithm, after all these years?

qubibi: It’s more like keep going back to it, rather than revisiting in the usual sense… Even back when it was first released in 2010, I felt hello world had so much potential, something worth digging into further. I couldn’t just end it there.

You know how when you watch a bonfire, you just find yourself staring at it, almost absentmindedly? I think I’ve always been trying to create something like that. That might be why I’ve kept coming back to it — sometimes to rethink color, sometimes simply to explore its depth. There’s still so much left to discover. I guess that’s the best way to answer the question.

KN: You describe ‘hello world’ as an evolving piece. You will probably keep working on it. How did it evolve over the years? I have the impression, for example, that the motion on the 2010 version was much faster.

quibibi: If you saw the 2010 version was faster, I think that’s really just within a margin of difference.

This new version largely re-creates what was originally made in Flash, but now in JavaScript — and of course, there are some limitations that come with that. There are also new elements added, naturally. But fundamentally, what hello world does is simply fluctuate between light and dark. That flickering itself is the work, in a sense. I don’t think the core of what it does has really changed.

It’s less about “evolution” and more about “metamorphosis.” At its root, there has always been this subtle restlessness; light shimmering, colors mixing chaotically, layers blending and dissolving into each other. What once appeared to be the subject might become the background, and vice versa. The work has always revolved around that ‘boundary’ though.

And as you keep watching, you realize that time has somehow been quietly absorbed. I think I’ve personally been saved by that experience — by having time absorbed away from me. That’s the deepest core of hello world, and that part has never changed.

hello world (2025)

KN: Are there any elements you’ve intentionally incorporated to bring about metamorphosis?

qubibi: You mean over the course of many years, right? When people keep engaging with a single work for so long, they themselves inevitably change. I get older, my perspective shifts, the things I look at evolve. So there are moments when I feel that what once felt pure to me back then might not feel the same now, and that makes me tweak things. I’m sure the work continues to change in that way. As long as I stay connected to it, those changes will keep happening. But what’s important, I think, is that my intention isn’t explicit — or if it exists, it stays deeply hidden beneath everything.

KN: What kinds of things in this work have changed, more specifically?

The key point of this work is that no one can really say what exactly has changed. Even though I’m the one writing the code, I can’t pinpoint it. But somehow, it just feels… better.

Because this work deals with time, I make tiny adjustments — maybe I tweak the color a little — then I experience the result and sense whether it feels right or not. I might watch it for ten minutes and think, this feels nice, or this version settles better. It’s something that can only be understood through that kind of slow observation.

If it were a painting, you might say, “some texture was added.” But hello world isn’t like that; it’s about flickering. It brightens, darkens, briefly brightens again, and darkens once more. And when that happens, I might think, “ah, that moment just now was good.”

It’s hard to define, but it’s closer to rhythm. Similar to music, in a way. So it’s not about the colors getting better or anything like that. It’s more like the time spent with it has become better or worse, and through repeating that process of quietly observing and adjusting, the work continues to metamorphose.

KN: With generative works, you can’t just say, “That moment looked great, let’s rewind and see it again”, right?

qubibi: I can’t. Even when I’m writing the code myself, I never really know what will happen after I make a change. I add a touch of red doesn’t mean red will necessarily appear there.

KN: So what are you actually doing, then?

qubibi: I honestly don’t know. I just try things, like slightly reducing the red component, and the next ten minutes of the piece can feel completely different from the ten minutes before.

Earlier I talked about how shifting distance in a gradient creates a boundary line. The same idea applies to time. There’s always a gap between what I do and the moment when the result appears. Between the action and the outcome, there’s time. And as long as that’s the case, all I can really do is wait and watch.

Of course, I understand the general tendencies, but even so, I’m combining elements within layers of randomness and probability. All I can do is observe what unfolds. I experience what emerges firsthand and sense whether it feels good or not. Sometimes the “bad” parts make the good parts shine even more. Like in Jaws movie — before the final climax, there’s that long, almost boring scene. But that dull moment makes what comes next so powerful. Right?

The same goes here. A stretch of darkness makes the sudden burst of brightness all the more beautiful. But even that isn’t something I’m controlling intentionally. I want the work to move as autonomously as possible. When intention shows through, it embarrasses me. It makes the artist too visible.

So I keep working, refining, without really knowing what exactly I’m improving. It’s a kind of dilemma. That said, it’s not like I’ve completely let go. I can’t discard my presence or intention as an artist. But if someone watching can find value in that ambiguity — in that unresolved tension — then I feel a kind of relief.

hello world (2025)

KN: The basic elements of animated generative art, I believe, are movement and time. Can you describe how you articulate them in hello world?

qubibi: Colors have hues, and when you rotate them, the colors begin to move. In other words, it’s not that the colors themselves are shifting in position, the colors themselves are changing. As each color changes, the whole thing appears to be in motion. And in this work, color is the shape.

It’s a simple, almost obvious idea, but that’s really the foundation — and what I’m doing is triggering those phenomena through various random values. Maybe that’s not directly related, but it’s something I can say for sure.

And when it comes to time, what’s most important is that the piece is moving now, being generated now. I believe animation is what makes that sense of “now” most perceptible.

For many people today, generative art might be more familiar in still-image form. But even if you say, “this was just generated,” the moment it stops moving, it already belongs to the past; it has been generated.

The truest form of generative art, I think, lies in that constant renewal, something being born right now, continuously updating itself.

That’s why, as a medium, animation feels the most powerful and most inherently “generative.”

If a work doesn’t have time, you can’t perceive that it’s moving or continuously forming. So movement, being animated is essential. Movement only exists because time exists.

In hello world, the play with color (shifting distances) eventually produced forms that resembled Turing patterns, but even in those patterns, I feel they must be in motion. They have to live through that continuous act of change, not in stillness.

Turing patterns on animals coatings.

KN: You have mentioned realizing that your generative work images were similar to the Turing patterns. Turing patterns are found on nature and maybe extend to ecosystems, even to galaxies. How do you feel about that?

qubibi: I originally knew nothing about Turing patterns. I only learned about them after creating hello world. I think there is a lot I have come to understand through the process of making the work itself.

The shapes of things in the world, including human forms, are all, I realized, created by natural principles.

Even if we take just one example, like a line, it cannot exist unless black follows white and white follows black again. The same goes for the forms of humans or animals.

Humans, for instance, have a form that is enclosed. Like a bag with a hole in the middle: the mouth and the anus are the only openings, and everything else is wrapped within. The shapes of living beings are built upon the basic laws of nature. I do not know if this applies to everything, but I feel it is something deeply fundamental.

What began as simple color play gradually led me to understand these things through the act of continuing to create. You could even say I have been taught by the process itself. I do not know much. I just keep learning, or rather, being taught, through making.

KN: Do you think your work has a meditative quality?

qubibi: In the end, yes, I think there is.

Depending on the nature of a piece, it either draws things in or sends things out. Some of my works are very much about output, about release. hello world, on the other hand, is the opposite. I want it to pull you in. There is something important, I think, about being absorbed by a work, about having your sense of time taken away by it.

It may end up feeling meditative, but I am not trying to make something meditative.

The name qubibi (首美) comes from the Japanese word kubi(首), meaning “neck,” the part that connects the body and the brain, or the hand and the arm. Then Bi(美) means art. In that sense, qubibi represents an artistic act that happens in between. I have never really been the type to make things in a direct way. I always feel like I am creating in the “in-between”.

So if there are messages or intentions in the work, I try to hide them as much as possible. I wrap them in layers, like a cocoon, until they are almost invisible. I never try to make the message easy to grasp. That tendency, the way I create, probably influences the nature of the work itself.

If a viewer reaches the point of thinking, “This work is saying this,” then there is only one answer. But my works exist in a state without an answer. That might be why they feel meditative. You cannot enter a meditative state if an answer is already there.

The idea of “dealing with time”, of “drawing in”, and the way the works are made, together, might be what give them that meditative quality.

KN: What/who inspires you? Are you familiar with avant-garde abstract films? Your work reminds me of Stan Brakage’s, such as Mothlight, that I was fortunate enough to watch in the cinema. It’s not so much that your works are similar; but rather my experience watching both works, were similar.

qubibi: It is only a guess, but I think Dusan Makavejev probably influenced me. When I saw his film Sweet Movie at seventeen, it was a real shock. In terms of being an avant-garde and abstract work, I think that film can be seen as related to what I do. And although he is not avant-garde, Federico Fellini as well.

When it comes to abstract film, there are many kinds of experimental works. For example, Norman McLaren made animations by scratching directly onto the film itself. That is a purely abstract form of animation. I learned about those historical examples later, as part of my own research, but the things that really influenced me were the ones I encountered when I was younger — game screens, or shocking films I saw as a teenager.

I am not the kind of person who works with a clear goal or artistic aim. It is more like, “I kept eating asparagus, and somehow this is what happened.” That kind of person. I never studied this in any formal or academic way.

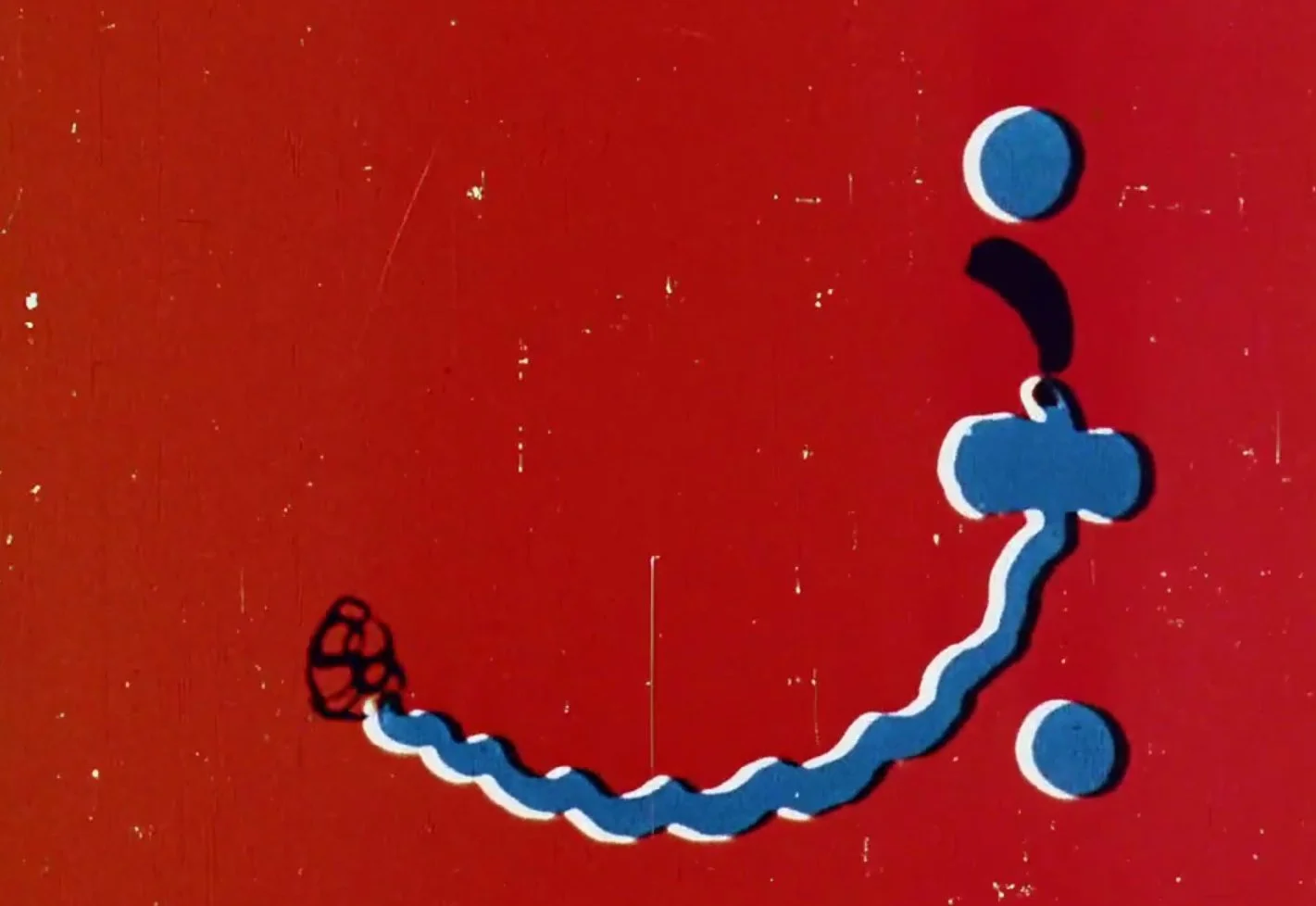

Boogie-Doodle (1941), by Norman McLaren

KN: I wonder if, working in this algorithm all these years, you were in a personal quest to understand some of the most profound questions: understanding the existence of life, the chaos and the order in nature, our place in all this as human beings. And somehow an attempt to re-engage with the unknown, with the mystery, with the magic of the world. Because looking at hello world, that’s where the work takes me.

qubibi: I’m really happy that you feel that way. Thank you. As for me, in the end, you might be right. But it’s not like I start out looking for something profound. It’s more that I just have to do it, almost out of a sense of duty. Though “duty” might sound off… maybe it’s more like respect. Or maybe, honestly, it’s just an obsession. Like, “I might be the one who can show this in the most compelling way, and I’m not giving that up to anyone else!” Something like that. Not that there’s really anyone else around anyway 😅

As things become more and more abstract, they get closer to the core, and it’s like an ultimate circle. It’s like, in the end, everything comes down to a circle.

So as an artist, I think it’s nice to move back and forth between the shallow and the deep!

KN: What do you search for, when curating still images and videos for this exhibition? Is it beauty, or something else?

qubibi: I’ll talk mainly about the collection called ‘hello world: Echos’, which consists of still artworks. Now that it’s over, I can say this — it was really tough. Mimizu, which was born out of hello world, has a certain density of lines that makes it visually appealing even as still images. But hello world isn’t like that. Hello world only comes alive when it’s in motion. So when I turn it into still images, something feels missing. It’s precisely because it moves that it works, yet I have to stop it. And when I try to add something to make the stopped image feel more complete, it starts to lose the movement and simplicity that define hello world. That’s a big dilemma. I’d be happy if everyone could enjoy seeing where that trial and error has taken the works.

hello world (2025)